Let’s talk about the films of 2011.

Below is my top ten list of the best films of the past year. What qualifies as a 2011 film? Any film that was released in South Africa in 2011, either cinematically or on DVD, or any film that rolled over from late 2010 into 2011 either cinematically or via a January DVD release. Also, any

film that came out in cinemas internationally in 2010 and had DVD releases in

2011 but never got any sort of release in South Africa. It’s unsettling how

many great movies never reach SA screens or stores, but I sort of understand

the thinking: who’s going to watch a Thai spiritual meandering on the big

screen? I have never understood why non-American reviewers use an American

release table for their lists.

Honourable mentions

Javier Bardem was quiet and sensitive in the downbeat

Biutiful, a trying but rewarding Spanish film about death that could only be made by Inarritu. Juliette Binoche was

luminous and vital in Kiarostami’s Certified Copy, a film that cleverly plays

with itself and audiences as it complicates the relationship between its two

central characters – or does it? I’m still not sure.

David O. Russell’s The

Fighter was far more than just another sports movie, with Christian Bale

winning an Oscar and Amy Adams doing supporting work. I still think that the

film was too condescending towards some of the female characters though. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part II was the perfect

finale to a great franchise, and Alan Rickman deserves special mention for what

he does with the character of Snape. If Part I was all tension and build-up,

Part II is a Helms Deep showdown featuring characters we’ve invested in for

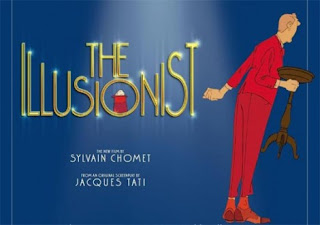

over ten years. The year’s best animated film is Sylvain Chomet’s heartfelt,

almost dialogue free The Illusionist. It tells the story of a stage magician

who is left behind by the world and its many new innovations and technologies,

and his new friendship with a young woman who finds herself traveling along

with him. It’s sad and beautifully animated – hand drawn.

The funniest film of the year was Brit Armando Iannucci’s In

the Loop, a rollercoaster political satire of great sophistication. The British

had a considerable Oscar presence in February, with Tom Hooper’s

delightful The King’s Speech taking Best Picture and Director, as well as Best Actor for Colin Firth. It’s the kind of film that the Brits make best: a

character-focused period drama with a sure positive payoff.

I have fallen in love with South Korean cinema, and Boon

Jong-ho’s Mother is one of the best, a gripping thriller about a mother (never

named in the film) driven to prove her mentally challenged son’s innocence as

he is arrested for the brutal murder of a young girl. The animated titular lizard

of Rango starred in the year’s second-best animated feature; any film that so

closely studies the conventions of the western and has time to reference

Apocalypse Now and Hunter S. Thompson is worth the effort. Another type of

animation featured in the rousing Rise of the Planet of the Apes, a

better-than-it-should-have-been prequel to one of the most famous science

fiction films. It features Andy Serkis as lead primate Caesar, and the great

John Lithgow as a father struggling with Alzheimer's while his scientist son

(James Franco) looks for a cure.

Finally, The Social Network is a near great film – a pity

that the final third runs out of steam as it fails to maintain the energy that

the first two thirds of the film showed. Fincher’s framing is, as always, worth

seeing in itself.

I do not have a “worst of” list, but surely the most

disappointing film of 2011 considering the talent involved is Joe Wright’s Hanna,

aka The Bourne Bore, aka I Was a Teenage Killer And Also I Can’t Blink.

And now, the best films of 2011 – that is, the best films I

saw in 2011 that coexist on a list where their positions might change in a day

or a year from now (with the exception of the top three, which will in all

probability stay the top three in that specific order). The list below proves

again, and it should come as no surprise, that the most fascinating films

happen when the psychology and philosophy of characters and viewers are

engaged. Keep in mind that it is impossible to see every single film, and I have missed many, including such potential greats as Incendies and In a Better World. So be it.

10. CARLOS

Edgar Ramirez is the star of Olivier Assayas’ film about the

infamous international terrorist. The five-hour plus film does not glamourise

its subject, nor does it pander to action or thriller conventions.

9. SKOONHEID

The best South African film in years, Oliver Hermanus’ drama

about desire and repression is unsettling and thought provoking. I know of many

people who do not like the film at all; I have a suspicion it’s more about these

peoples’ feelings towards the film’s content than the film itself. Seek it out,

but not for sensitive viewers.

Harrowing Chinese anti-war film about the Rape of Nanking;

the black-and-white imagery is uncompromising, and the film not easily shaken.

Again, not for sensitive viewers, but as with Skoonheid, nothing is

sensationalised.

7. DRIVE

A smooth, meticulous action thriller featuring the return of

the mythological hero (Ryan Gosling). As usual, the hero’s trouble begins when

he pursues a relationship with (literally) the girl next door (Carey Mulligan).

One of the most beautifully shot films of the year, and with a fitting

soundtrack. This bodes well for director Nicholas Windig Refn. The film's most memorable asset is Albert Brooks as the cold blooded Rose. May the Oscar come his way.

6. BLACK SWAN

Natalie Portman received a well-deserved Best Actress Oscar for

her portrayal of the steadily-losing-her-mind ballerina. This nightmarish and claustrophobic thriller demonstrates that Darren Aronofsky

remains one of the most exciting contemporary American filmmakers.

Xavier Beauvois’ Cannes favourite is a moving, human tale of

ethics, religion and politics set in an increasingly unstable Algeria in the

1990s. Some have criticised the film for what the characters do towards the

end, but to do that denies the quiet force of one of the most visually

impressive films of 2011. It is a film to revisit and cherish.

4. DOGTOOTH

Greek filmmaker Giorgios Lanthimos has made, I think, the definitive dysfunctional family

drama. The less you know about the film beforehand the better, and

with its themes of incest and the gross manipulation of others, it makes for

selective viewing. Of all the films on my list, this one is the least likely to

work for anyone. Watch at own risk. Whether you adore or detest it, you won't be able to forget it.

I gave Uncle Boonmee a negative review earlier this year,

and the joke is on me, the egg on my face: it is, in fact, a masterpiece. It

was my own lack of understanding and, I suppose, my mood at the time of the

original viewing that lead to my initial negative write-up. I’m not going to

re-review the film, or edit my original review, so I’ll say it here: I was wrong, and now I can see. Uncle

Boonmee is deeply spiritual (mortality, reincarnation, the presence of the

dead among the living) and as deeply concerned with an increasingly

materialistic Thai society in general. From now on, I’m rooting for Team

Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

2. TRUE GRIT

Can the Coen brothers do no wrong? No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading (which gets even better the more you watch it), the

existential hilarity of A Serious Man, and now this gripping remake of a John

Wayne original. One the one hand True Grit is a well-crafted western with The

Dude himself, Jeff Bridges, proving an unconventional and flawed heroic figure

for young Hailee Steinnfeld’s spunky protagonist. On the other, True Grit is a

typically Coen film in terms of quirkiness, characterisation and framing, which

results in a genre film littered with moments of death and hilarity. It happens to have my favourite opening and closing scenes of all

films on this list.

1. TREE OF LIFE

Malick’s autobiographical-cosmological family drama is the

most divisive film since Antichrist. Either people loved it, and loved it

deeply, or they hated it, and hated it with much passion. I’m not going into

the debate here except for saying that I understand where and how the film

loses so many people, and that they all have my sympathy. An ambitious, life-affirming masterpiece by a master filmmaker.